Scratch Pad and Negotiation Literature

Miscellenaous Notes on the topicKey Terms

Distributive Justice (DJ) - perceived fairness of how rewards and costs are shared by (distributed across) group members

Procedural Justice (PJ) - the idea of fair processes, and how people's perception of fairness is strongly impacted by the quality of their experiences and not only the end result of these experiences.

Reciprocity - mutual responsiveness to each other's concessions.

Negotiation - are dynamic processes during which the negotiators:

- communicate

- raise threats or argue to influence each other

- exchange offers and make concessions

to reach an agreement. Individuals must balance two competing processes: value creation and value claiming.

Toward a Process Model of First Offers and Anchoring in Negotiations1

-

Tversky and Kahneman (1974) define the anchoring effect as an insufficient adjustment from an initially obtained value (anchor).

-

Later research argued for the selective accessibility perspective, in which information is recalled and interpreted selectively to fit the anchor (Chapman & Johnson, 1999; Mussweiler & Strack, 1999, 2001; Strack & Mussweiler, 1997).

-

The authors argued that it is not the mere value of the anchor but also its applicability to the problem. The selective accessibility model is currently the dominant view of anchoring mechanics (Furnham & Boo, 2011).

-

Jeong et al. (2019) found that first offers in a tough and firm language led to better counteroffers compared to warm and friendly first offers.

Talking It Through: Communication Sequences in Negotiation 2

Patterns of reciprocity are common in negotiation, whereby counterparts respond-in-kind to both distributive and integrative tactics

A Note on Multi-Issue Two-Sided Bargaining: Bilateral Procedures 3

- In particular the note examines the possibility that group heterogeneity (conflicting priorities) may be exploited in order to gain a better settlement.

Standardized interpolated path analysis of offer processes in e-negotiations4

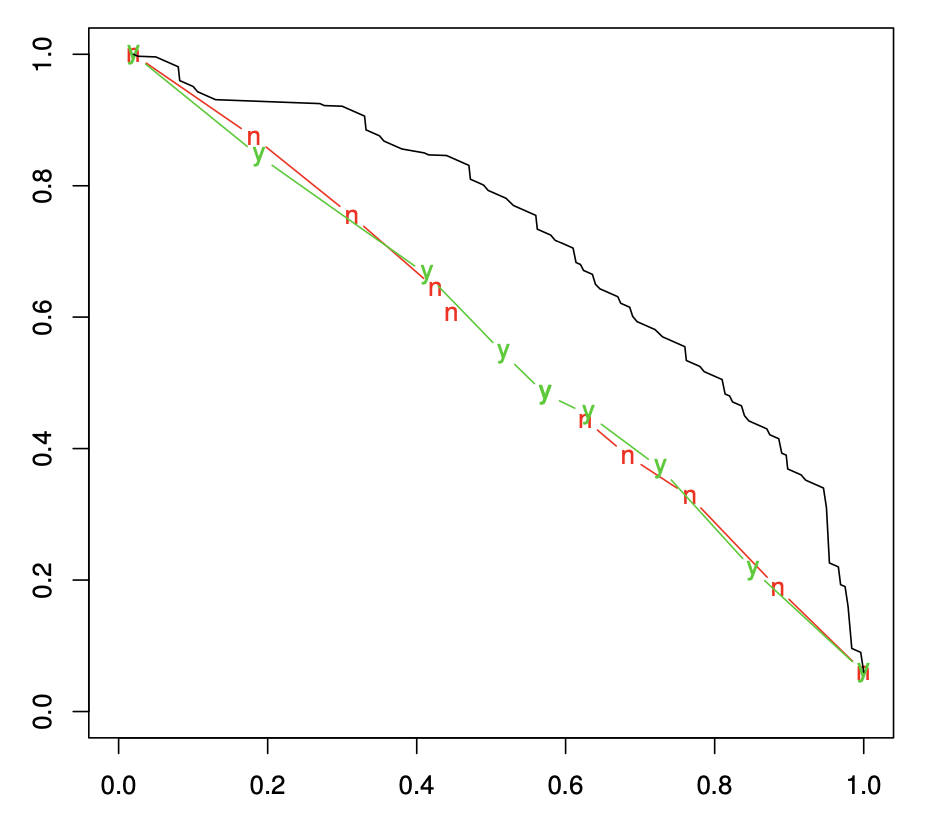

The figure shows the average negotiation path in utility space of two parties for successful (marked by “y”) and failed (marked by “n”) negotiations, as well as the Pareto efficient frontier of the problem. It is quite obvious from this graph that on average subjects were strongly influenced by a fixed pie assumption [3] and failed to identify possibilities for mutual benefit

Negotiation Offers and the Search for Agreement5

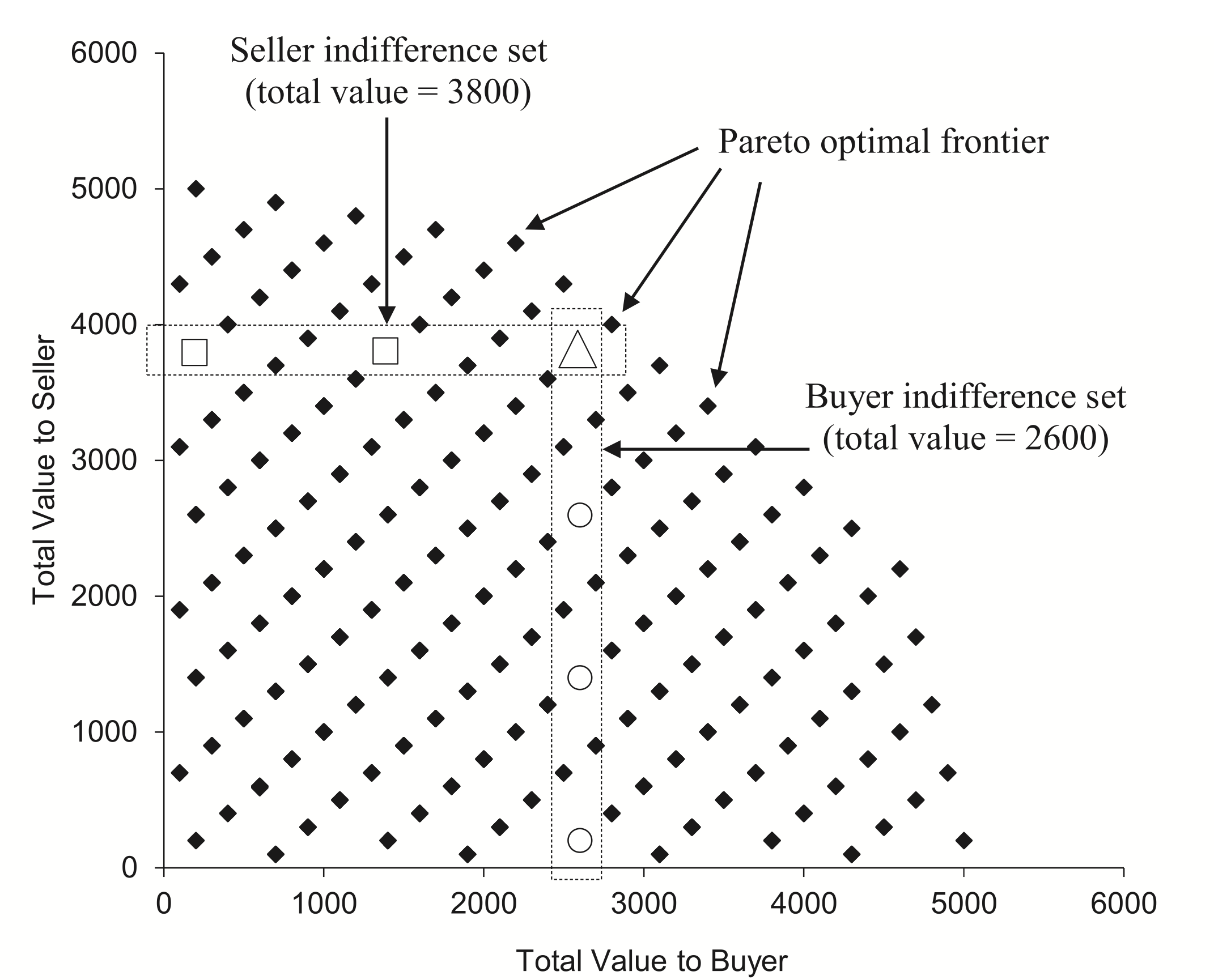

- Negotiation offer spaces are often displayed in terms of value as a two-dimensional "joint-sum plot" where all possible comprehensive offers are mapped into the respective values to each negotiator.

-

How do negotiators jointly search a large offer space for potential offers?

-

How do negotiators select the offers they propose within that search?

-

How do these offers converge toward an agreement?

-

When comparing offers, we also rely on content and value. For each we define when components of offers are the same (equivalence) and if not, how far they are apart (distance).

Propositions

- Negotiators will reduce the complexity of the search by considering only a subset of potential offers.

- Offers incorporate information regarding the value of prior offers and the content of prior offers.

- In general, negotiation will tend to evolve by phases evidenced by offers: one is Exploratory embodied by value-based exploratory search; another is Refinement embodied by content-based refinement search.

- Exploratory search is value-based, dominated by partial offers, influenced more by individual value and less by asserted content of offers.

- Refinement search is content-based, dominated by comprehensive offers, influenced more by asserted content of offers than by individual value.

- A refinement set is the primary mechanism by which negotiators coordi- nate to reduce the search effort within an offer space.

- Content Similarity Heuristic. Negotiators will respond to comprehensive offers with those that tend to be similar (in terms of content options selected) to imme- diately preceding offers (their own or the other party's).

- Content proximity bias. Refinement sets (as common ground compo- nents) tend to evolve by relatively small changes in content proximity (issue options) that serve to maintain the continuity of joint attention and to reduce disturbance to the current state of the common ground.

- Negotiations characterized by initial refinement sets that are farther from the Pareto optimal frontier and early or inflexible proximal search are less likely to reach optimal agreements.

- Search patterns that systematically extend the refinement set are more likely to reach optimal agreements.

- Reorientations of the refinement set should increase the likelihood of reaching optimal agreements.

Being Tough or Being Nice? A Meta-Analysis on the Impact of Hard- and Softline Strategies in Distributive Negotiations.6

- A negotiation is commonly understood as a communication between parties with perceived divergent interests to reach agreements on the distribution of scarce resources. It thus involves protagonists who depend on one another for achieving outcomes they cannot reach on their own.

- However, these protagonists also tend to be motivated to maximize their individual outcomes. Therefore, in distributive negotiations, they typically face a conflict between cooperating with the other party (e.g., concede to not endanger an agreement) and competing with the other party (e.g., be reluctant to concede to maximize individual benefits). This basic conflict between cooperation and competition has been termed the negotiator's dilemma.

- In distributive negotiations, where the protagonists negotiate only one issue (e.g., price of an item in a buyer–seller negotiation), each concession is automatically a loss for the conceding party and an equivalent gain for the receiving party. As negotiation parties have divergent interests, they normally start from opposing positions, and at least one party has to concede once or several times to make an agreement possible. It could thus be argued that negotiators face a concession dilemma because they do not want to give up too much value by conceding unilaterally, but at the same time they have to sufficiently concede to realize an agreement that secures more value than they can achieve single-handedly.

- Conventionally, the expected advantages of hardline compared to softline bargaining strategies are theoretically derived from level of aspiration theory (Siegel & Fouraker, 1960). Level of aspiration theory argues that negotiators enter a negotiation with a certain level of aspiration (i.e., an aspired level of individual utility), which can be based on different considerations (e.g., financial need, knowledge or assumptions on the total amount of payoff, etc.). The initial level of aspiration is adjusted in the course of the negotiation by experiences of success and failure. According to level of aspiration theory, receiving an aggressive first offer and/or rare or insignificant concessions should be experienced as failure considering the viability of one's own initial aspiration level. This failure experience should lead to a reduction in the initial aspiration level. In other words, level of aspiration theory suggests that an aggressive initial offer and minimal concessions communicate a focal negotiator's intention to make a massive profit and not to give up any more value than necessary. When she or he follows such a strategy and leaves no doubt about her or his intention, the opposing party's level of aspiration should diminish. Consequentially, the opposing party should be more likely to concede to obtain an agreement (Siegel & Fouraker, 1960). Usually, negotiators value agreements over nonagreements because the former provide outcomes that cannot be achieved without an agreement.

- Negotiators pursuing a hardline strategy are rather recommended to walk the fine line of showing a firm resolve and appearing to be fair at the same time by offering few and small, but timely, concessions.

- The rationale of softline bargaining strategies can be theoretically derived from the graduated reciprocation in tension-reduction model (Osgood, 1962). This model stresses the importance of unilateral concessions to instigate a “give-and-take” among the negotiating parties. According to the model, it is, however, important that the opposing party does not attribute received concessions to weakness. To the contrary, concessions should be clearly communicated as reflecting the focal negotiator's cooperative intentions to initiate a circle of mutual concessions based on reciprocity. In the resulting atmosphere of mutual trust, both parties avoid the costs of lengthy and competitive zero-sum bargaining, in which each concession is typically perceived as a substantial loss. Instead, the perception of the negotiation is transformed into a problem-solving situation, in which both parties work toward a solution in the spirit of “splitting the difference” from their initial positions.

Footnotes

-

Lipp, Wolfram and Smolinski, Remigiusz and Kesting, Peter, Toward a Process Model of First Offers and Anchoring in Negotiations (July 15, 2022). Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, Forthcoming , Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4163493 ↩

-

Adair, Wendi L., and Jeffrey Loewenstein. "Talking it through: Communication sequences in negotiation." Handbook of research on negotiation. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2013. 311-331. ↩

-

Fershtman, Chaim. "A note on multi-issue two-sided bargaining: bilateral procedures." Games and Economic Behavior 30.2 (2000): 216-227. ↩

-

Vetschera, Rudolf, and Michael Filzmoser. "Standardized interpolated path analysis of offer processes in e-negotiations." Proceedings of the 14th Annual International Conference on Electronic Commerce. 2012 ↩

-

Prietula, Michael J., and Laurie R. Weingart. "Negotiation offers and the search for agreement." Negotiation and Conflict Management Research 4.2 (2011): 77-109. ↩

-

Hüffmeier, Joachim, et al. "Being tough or being nice? A meta-analysis on the impact of hard-and softline strategies in distributive negotiations." Journal of Management 40.3 (2014): 866-892. ↩